Following Brian Anse Patrick, I have referred to the period from roughly 1850 to 1980 as the “Restricted Era” in gun carry in the United States. This reflects the spread of outright bans on concealed carry, as well as the implementation of discretionary, “may issue” permitting systems.

However, restricted does not mean “never done.” Reflecting on his time as a police officer in Tennessee in the 1970s, gun trainer Tom Givens said it was so common for people to carry guns in their cars that when he pulled someone over he did not ask, “Do you have a gun in your car?” He asked, “Where is the gun in your car?”

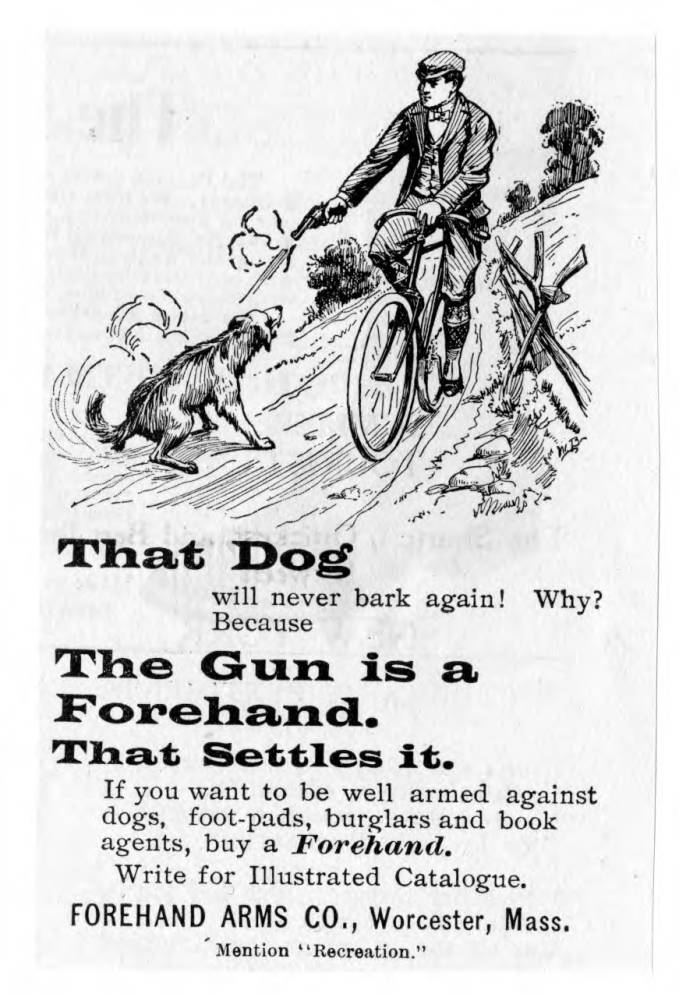

The existence of laws against some behavior is not the same as people following or officials enforcing those laws. This is especially true when there is a strong motivation to engage in the prohibited behavior (think “Prohibition”). So, if the late 19th century was part of the restricted era, it was also in the words of historians Lee Kennett and Jules LaVerne Anderson, “a gun-toting era.”

Here I excerpt some interesting passages about this gun-toting era from Kennett and Anderson’s 1975 book, The Gun in America: The Origins of a National Dilemma.

Reminiscent of events of 2020, Kennett and Anderson report:

In the wake of the Chicago Riots of 1877, the Tribune reported that “every man who could beg, buy, or borrow a revolver carried it,” with total disregard to the local ordinance against concealed weapons.

p. 147

The authors continue:

If sudden outbreaks spurred mass arming for the moment, there is evidence of a steady increase in the general tendency to go armed. . . . Over the years it was reduced in bulk and became easier to carry concealed. The pocket pistol became a popular item, with none more diminutive and deadly than those of Henry Deringer.

p. 147

At the same time concealed carry bans were spreading through the rural southern states, the desire to carry concealed was growing in the urban North:

The pocket pistol was essentially the weapon of a more civilized and urban community, where danger came in close quarters and was part of the society itself. The general tendency to keep arms or carry them on the person may well be linked to what has been called the “urban explosion” that transformed American cities in the period 1820 to 1860. Its mechanism of everyday law enforcement did not keep pace with its growth, so the inhabitant felt an increased need to fend for himself in this regard. The sense of personal insecurities in the face of crime probably did more to foster the trend toward personal armament than anything else, with sporadic outbreaks of mass violence accelerating the process from time to time.

p. 148

Of course, as in today’s shall issue gun-toting era, only a minority of gun owners carry in public:

It is doubtful if anything more than a small minority of Americans went constantly armed. It was estimated in 1877 that one Chicagoan in ten would be found with a pistol concealed on his person.

p. 157

Of course, whether 10% of Chicagoans carrying concealed pistols is a low or high proportion is a matter of expectations and judgement.

Kennett and Anderson quote a book published in 1875 with a remarkably contemporary title: The Pistol as a Weapon of Defense in Its Home and on the Road. How to Choose It and How to Use it (New York: Industrial Publications Co.).

Writing in 1875, the anonymous author of a guide to the purchase and use of pistols hardly dealt with a controversial subject. He called the pistol a superlative instrument for self-defense, since it “renders mere physical strength of no account, and enables the weak and delicate to successfully resist the attacks of the strong and brutal.”

p. 157

The reasons concealed carry bans were hard to enforce are similar to the reasons people give for liberalizing concealed carry laws in the contemporary era:

There was a difference between laws passed and those enforced. Jordan has stated: “Three dynamic, viable factors thwarted the law. First, men liked weapons, wanted weapons, enjoyed the power that weapons lent them, and insisted on having and using and caring and handling them as they please. Second, a good many gentlemen of one kind or another – some jurist and some vagrants were disciples of a religion known as the ‘higher law.’ Third, personal weapons, upon occasion, were urgently needed for self-defense.” For these reasons laws involving the regulation of concealed weaponry were difficult to enforce.

p. 160, quoting Philip D. Jordan, Frontier Law and Order (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1970), p. 7

And, as with today, when seconds count, police are just minutes away:

The [New York] Tribune’s survey of 1903 also indicates quite clearly that honest citizens often went armed. Those who traveled at night or with sums of money felt much safer with revolvers in their pockets. … Most felt they needed them for self-defense, holding that the public guardians of the peace could not always be relied upon to protect life and property.

p. 179-80

Reading Kennett and Anderson’s book is a good reminder to me that, even thought the center of gravity of gun culture has shifted over time toward self-defense, self-defense has always been an important part of American gun culture.

Raises the issue of granting “longstanding” restrictions on individual liberty, particularly in terms of gun rights, some sort of judicial deference. Legislatures can make all sorts of restrictions, which the bulk of the generally and meaningfully “law-abiding” population will feel free to ignore, to passively and peacefully resist, as they see fit.

LikeLike

I like also that the authors address the lack of enforcement.

LikeLike

[…] Late-19th Century America as a “Gun-Toting Era” — Gun Culture 2.0 […]

LikeLike